Japan's Prime Minister Kishida Fumio has announced the tsunami-damaged Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant will begin releasing treated wastewater into the Pacific Ocean from Thursday.

The plan has been in the works since 2018, and was approved by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) early last month.

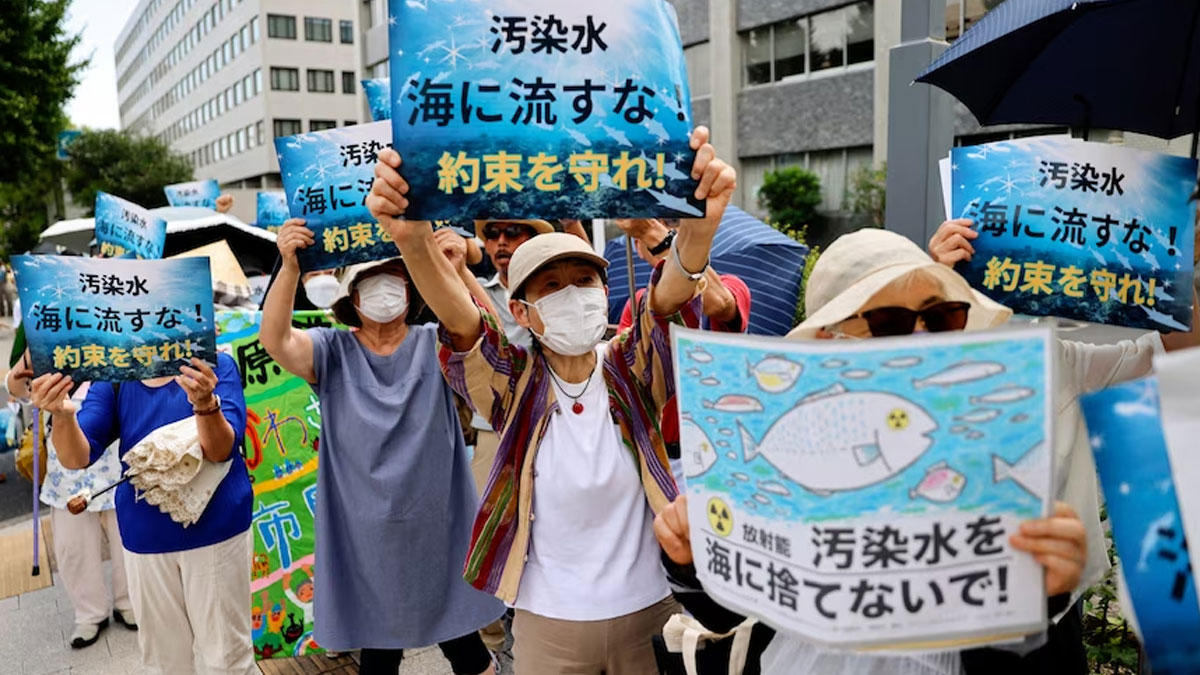

But the issue nevertheless remains controversial, with the water's release facing intense opposition both at home and on the world stage.

Here's exactly what the government is planning to do, what opponents of the release say, and why the government is pressing ahead despite the political headwinds.

What is the government planning to do?

After the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant was heavily damaged by an earthquake and tsunami in 2011 — leading to three reactor meltdowns and the release of radioactive isotopes into the air — the Japanese government had to decide what to do with the water used to cool the reactors in the disaster's aftermath.

The release of coolant water (after treatment) is routine for nuclear plants all over the world. But because water at Fukushima was poured directly onto the melting reactors, instead of being circulated around them, it became loaded with a much higher-than-usual concentration of radioactive compounds, called radionuclides.

More than 1.3 million tonnes of water have since accumulated at the power plant, where it is being held in massive tanks that the plant's owner, the Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO), says will be full by the end of next year.

The government in 2021 confirmed it would go ahead with a plan to remove most of the radioactive compounds from the water using an advanced filtration process and release it into the ocean, via an underwater tunnel emerging more than a kilometre off Fukushima's coast.

The one compound that cannot be filtered is tritium, a hydrogen isotope that is extremely difficult to separate from water.

Instead, the government proposes to heavily dilute the water to reduce its tritium levels to well within acceptable international standards for drinking water, and release a maximum of 500,000 litres per day.

What do the plan's opponents say?

Opposition to the government's plan is wide-ranging, from scientists who question the environmental value of large-scale dilution to local fishermen who fear renewed reputational damage just as the industry is beginning to recover from the initial disaster.

Most of the concern is centred around the government's inability to filter out tritium from the wastewater before its release.

Tritium has been found to cause damage to DNA, although it is generally accepted to only pose a risk to humans if ingested in much larger doses than what the government is proposing to release.

Scientists have pointed out that it is difficult to track the effect of low-dose exposure to tritium and other radionuclides over a long period of time.

A large portion of the Japanese public is also wary of accepting assurances from TEPCO, which has previously been less than forthcoming with uncomfortable truths about its practices following the Fukushima disaster.

The company only admitted in 2018 that the stored wastewater still contained radioactive compounds, after initially saying they had successfully been filtered out.

It had also previously failed to reveal to the public that contaminated water had leaked into the ocean, because it did not want to alarm the public until it was sure there was a problem.

How much support does the plan have?

A recent poll, conducted in early July by the Japan News Network, showed just 45 per cent of people in Japan support the government's plan.

While that's greater than the 40 per cent who oppose it, it's a startlingly low level of support for a proposal for which the government has spent months trying to win over public opinion.

On another front, the wastewater release has raised concerns in Pacific countries, even those as far away as Papua New Guinea and Solomon Islands.

It has been heavily criticised in particular by Beijing, which has banned seafood imports from 10 Japanese prefectures including Fukushima.

Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Wang Wenbin in June said Japan was treating the ocean as its "private sewer", and had chosen the underwater release purely because it was the lowest-cost option.

While Japan denies this is the case, it has also dismissed a plan that has been gaining approval among the local population — building massive new underground reservoirs that would store the contaminated water until it loses radioactivity — due to it being too expensive.

Why is the government pushing ahead?

Despite the contentious nature of the plan, and a number of delays in announcing the start date, Japan's government has made it clear that the wastewater release itself will not be postponed.

The government says the water tanks need to be emptied so they can be moved to make room for new facilities to help with the plant's decommissioning process, which is part of its long-term plan to reopen the area to housing.

TEPCO also says the risk of another earthquake means the current situation is untenable, as the tanks mostly contain untreated water and an unplanned leak would be far more dangerous and environmentally harmful than a controlled release of treated water into the ocean.

The government has launched a massive public information campaign in support of the wastewater release, including advertising, festivals, high school forums and a live stream of fish swimming in a tank of treated wastewater.

Mr Kishida also met with representatives of the fishing industry on Monday, assuring them the government would allocate extra funds to counter "harmful rumours" about their product's safety.

By Andrew Thorpe

Original article link: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-08-22/fukushima-wastewater-decision-explainer-fumio-kishida-nuclear/102754932

Stay tuned for the latest news on our radio stations