On the Swedish coast of the Baltic Sea, in the city of Sundsvall – home to the country's pulp and paper industry – a team of scientists, chemists, entrepreneurs and textile manufacturers are celebrating a milestone birthday, under a banner which features the slogan "#SolutionsAreSexy".

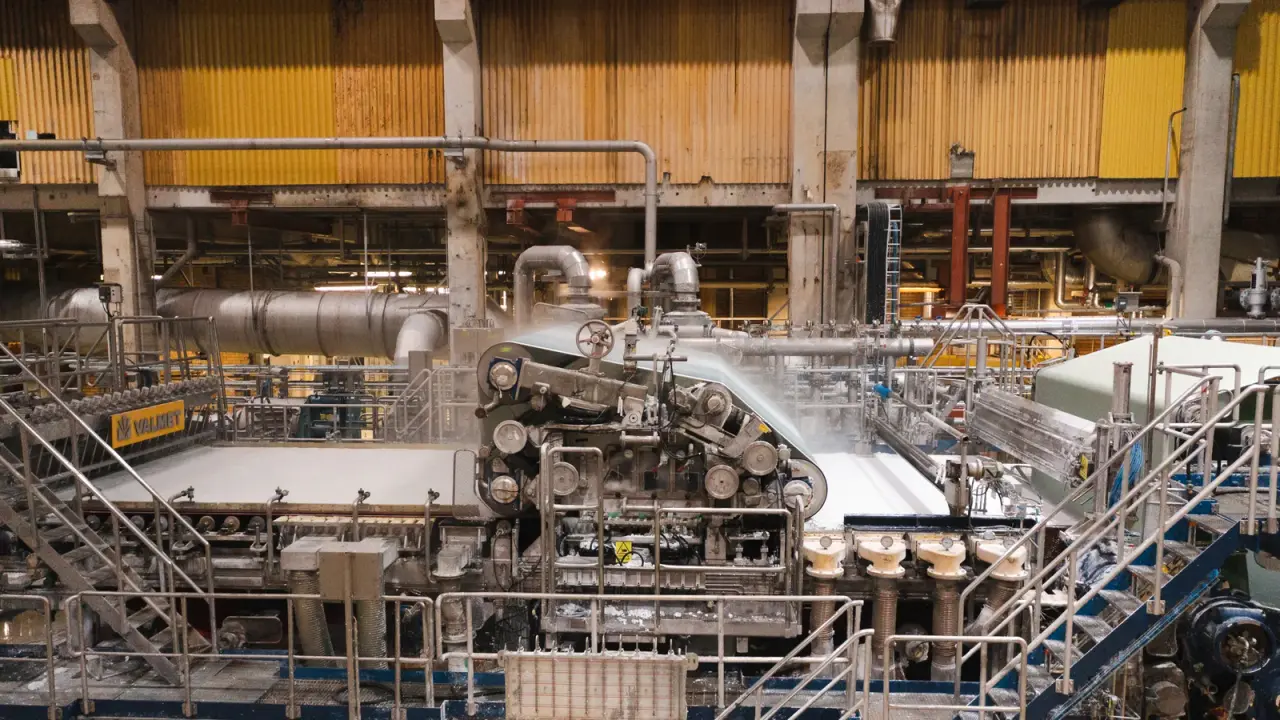

The Swedish pulp producer Renewcell has just opened the world's first commercial-scale, textile-to-textile chemical recycling pulp mill, after spending 10 years developing the technology.

While mechanical textiles-to-textiles recycling, which involves the manual shredding of clothes and pulling them apart into their fibres, has existed for centuries, Renewcell is the first commercial mill to use chemical recycling, allowing it to increase quality and scale production. With ambitions to recycle the equivalent of more than 1.4 billion T-shirts every year by 2030, the new plant marks the beginning of a significant shift in the fashion industry's ability to recycle used clothing at scale.

"The linear model of fashion consumption is not sustainable," says Renewcell chief executive Patrik Lundström. "We can't deplete Earth's natural resources by pumping oil to make polyester, cut down trees to make viscose or grow cotton, and then use these fibres just once in a linear value chain ending in oceans, landfills or incinerators. We need to make fashion circular." This means limiting fashion waste and pollution while also keeping garments in use and reuse for as long as possible by developing collection schemes or technologies to turn textiles into new raw materials.

Each year, more than 100 billion items of clothing are produced globally, according to some estimates, with 65% of these ending up in landfill within 12 months. Landfill sites release equal parts carbon dioxide and methane – the latter greenhouse gas being 28 times more potent than the former over a 100-year period. The fashion industry is estimated to be responsible for 8-10% of global carbon emissions, according to the UN.

Just 1% of recycled clothes are turned back into new garments. While charity shops, textiles banks and retailer "take-back" schemes help to keep those donated clothes in wearable condition in circulation, the capabilities of recycling clothes at end-of-life are currently limited. Many high street stores with take-back schemes, including Levi Strauss and H&M, operate a three-pronged system: resell (for example, to charity shops), re-use (convert into other products, such as cleaning cloths or mops) or recycle (into carpet underlay, insulation material or mattress filling – clothing is not listed as an option).

Much of the technical difficulty in recycling worn-out clothes back into new clothing comes down to their composition. The majority of clothes in our wardrobes are made from a blend of textiles, with polyester the most widely produced fibre, accounting for a 54% share of total global fibre production, according to the global non-profit Textile Exchange. Cotton is second, with a market share of approximately 22%. The reason for polyester's prevalence is the low cost of fossil-based synthetic fibres, making them a popular choice for fast fashion brands, which prioritise price above all else – polyester costs half as much per kg as cotton. While the plastics industry has been able to break down pure polyester (PET) for decades, the blended nature of textiles has made it challenging to recycle one fibre, without degrading the other. (Read more about why clothes are so hard to recycle.)

By using 100% textile waste – mainly old T-shirts and jeans – as its feedstock, the Renewcell mill makes a biodegradable cellulose pulp they call Circulose. The textiles are first shredded and have buttons, zips and colouring removed. They then undergo both mechanical and chemical processing that helps to gently separate the tightly tangled cotton fibres from each other. What remains is pure cellulose.

After drying, the pulp sheet feels like thick paper. This can then be dissolved by viscose manufacturers and spun into new viscose fabric. Renewcell says it powers its process using 100% renewable energy, generated using hydropower from the nearby Indalsälven river.

As the most common manmade cellulosic fibre (MMCF), viscose is popular because of its lightweight, silk-like quality. MMCFs have a market share of about 6% of the total fibre production. Dissolving pulp cellulose is used by the textiles industry to make around 7.2 million tonnes of cellulosic fabrics each year, according to Textile Exchange. But the majority comes from wood pulp, with more than 200 million trees logged every year, according to Canopy, a US non-profit whose mission is to protect forests from being cut down to make packaging and textiles, like viscose and rayon. Not only does Renewcell's technology help keep forests intact, it also produces a higher pulp yield. "A tree is made up of different parts, including cellulose, but about 60% of it is non-cellulose content that you can't do much with," says Renewcell strategy director Harald Cavalli-Björkman. "Aside from a small loss, all of the waste cotton we use is turned into pulp."

The mill has a contract with Chinese viscose manufacturer Tangshan Sanyou Chemical Industries for 40,000 tonnes per year, and is in talks with other large viscose manufacturers, such as Birla in India and Kelheim Fibres in Germany. Swedish fashion brand H&M, which produces three billion garments per year and is an early investor in Renewcell, has signed a five-year, 10,000 tonne deal with the pulp mill – the equivalent of 50 million T-shirts. Zara also partnered with Renewcell on a capsule collection in 2022.

"We want to build more mills," says Cavalli-Björkman, adding that Renewcell hopes to be able to recycle 600 million T-shirts within a year – the equivalent of 120,000 tonnes of textile waste and a doubling of its current capacity. "But that is still very little compared to the global market for textile fibres. By 2030, we're aiming for a capacity of 360,000 tonnes."

But Renewcell's technology has limitations: it can only recycle clothes that are made of cotton, with an allowance of up to just 5% non-cotton content. "Partly, it's because it's difficult to separate polyester, too much of which affects product quality, but also, we want to make sure we have a decent yield coming out the other end," says Cavalli-Björkman. "With the exception of things that require exceptional durability like workwear or specific properties like waterproof clothing, the only reason for using polyester is because it's cheap – yet with a huge cost to the environment. We'd like to turn back that tide, to get clean materials and fewer blends into circularity."

Cavalli-Björkman says that fast fashion's reliance on low-cost synthetic fibres has affected consumer attitudes towards the value of clothes. "Before we had industrialised textiles production, people took care of their clothes," he says. "They repaired them because clothing was an investment. Today, clothing is so cheap that the perception is, you can always grow some more cotton, you can always pump some more oil – that's far easier than putting the effort into creating a quality product from something that already exists and could stay in circulation."

Natascha Radclyffe-Thomas, professor of marketing and sustainable business at the British School of Fashion, agrees that it's a question of value. "We often feel like we can recycle our way out of waste, and while recycling is a key part of the solution, it's not the starting point," she says, pointing to overproduction and consumption as root causes of the fashion industry's waste problem. Inexpensive, low-quality clothes mean it is often cheaper for consumers to buy a new outfit, rather than getting an item repaired.

But other companies are focusing their efforts on synthetic and blended materials which are widely used by fast fashion brands.

Worn Again Technologies, based in Nottingham in the UK, raised £27.6m ($34.2m) in October to build a textile recycling demonstration plant in Winterthur, Switzerland, for hard-to-recycle fabric blends, such as clothes made from polyester and cotton mixes. Rather than operating its own commercial-scale mill, Worn Again (in which H&M has also invested) is developing a process to be licensed to large-scale plant operators around the world, due to be launched in 2024.

As its feedstock, Worn Again uses textiles made from pure polyester or poly-cotton blends, with up to 5% tolerance of other materials excluding metal, such as zips and hardware. There are two output streams. One is a PET pellet, which has the same chemical structure and make-up as virgin PET, to be made into recycled polyester. The other is similar to Renewcell's: once the cotton is separated from the poly-cotton blend, the cellulose is purified and recaptured in the form of a pulp or cellulosic powder, to be made into viscose.

Source: BBC

Stay tuned for the latest news on our radio stations